Woodlands can be mysterious places. Birds hidden in the trees, with only their song to betray their presence. Hunters hidden away until the night when a new realm of creatures come out to play.

Monitoring wildlife can be an exciting way for us to understand our land’s wild secrets. It’s also vital for us to understand the health of the ecosystem. Diverse ecosystems are important for the health of our planet, and all animals (including us) that inhabit it.

Biodiversity, which is defined as the variability among living organisms in an ecosystem, can be measured in various ways, and at different levels of depth. One way to measure biodiversity is to assess the species richness of an ecosystem, which is the total number of distinct species within a local community. It would take many hours, days, or even months for us to capture every species found in a given area, especially small insects which can be extremely diverse within a small area.

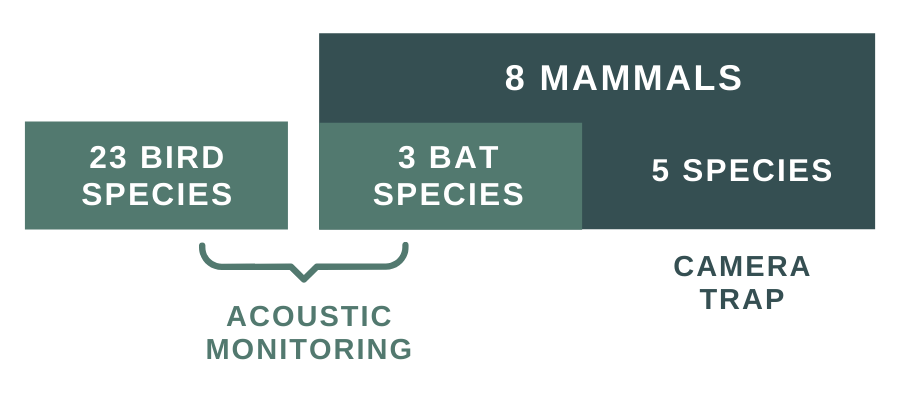

We are currently using passive monitoring devices, detecting bird and mammal species, many of which can be considered key indicator species whose presence or abundance can reflect the health of the ecosystem.

Here we share the findings of one of our test sites, a welsh woodland in Powys, Wales. The woodland is undergoing a change, replacing several hectares of existing conifer trees with numerous native species, and we hope to track the changes in species richness through this process. 31 species were detected using the methods described below during the period between 31st July – 11th September 2021. The most interesting species were the birds – Hawfinch, Wood Warbler and the mammal – Pine Marten.

- Mammals: Camera traps were used across the site to detect small land-based mammals, and acoustic monitoring at ultrasonic frequencies were used to identify bat species through their echolocation calls.

- Birds: Acoustic monitoring was also used to identify bird species through their bird song and calls. Some of the audio of species recorded can be heard in the video below.

Species Overview

Mammals

5 mammal species (and one bird species) were detected using camera traps, although the pine marten highlighted below will need to be confirmed with further monitoring due to the blurred capture.

Badger

Squirrel

Hare

Pine Marten

Fox

Pheasant

Bats

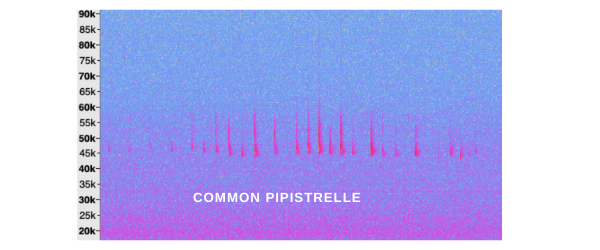

Different species of bat can be determined by the characteristics of their echolocation signals and ultrasonic calls.

Using acoustic monitoring devices, recording at high frequencies, we can detect species through analysis of the signals recorded. There are limitations to this method, as unusual environments or locations can cause variations in the signals produced. In woodland environments, species can appear similar as they adapt their signal to suit the structure of the environment, and misidentification can occur.

However, several key species can be identified, including several indicator species. Due to their reliance on significant insect populations, their population can reflect the health of the local environment. There are several indicator bat species in the UK, including lesser horseshoe bat, common pipistrelle, soprano pipistrelle, Daubenton’s bat, Natterer’s bat, serotine and noctule – three of these species have been detected in the woodland (highlighted in bold).

The following bat species were detected:

| Species | Description | Weight/Wingspan |

| Common Pipistrelle (Pipistrellus pipistrellus) | The common pipistrelle is our smallest and most common bat. They roost in tree holes, bat boxes and even the roof spaces of houses, often in small colonies. | 3-8g / 20-23cm |

| Soprano Pipistrelle (Pipistrellus pygmaeus) | Hard to differentiate from its cousin, the common pipistrelle bat, this widespread species hunts close to water and can be found in woods and gardens. It can be differentiated by the frequency of its echolocation calls (55KHz, higher than the common pipistrelle at 45KHz) | 3-8g / 20-23cm |

| Natterer’s bat (Myotis nattereri) | The Natterer’s bat is a medium-sized bat. They feed on moths, midges and other flying insects, but also forage on beetles and spiders that they take directly from foliage. Their flight is relatively slow and they can be found hunting over water and among the trees after sunset. | 7-12g / 24 – 30cm |

The common pipistrelle can eat 3,000 gnats in a single night. In October, common pipistrelles become less active and by December will have entered full hibernation. The bats normally hibernate in buildings, taking advantage of the warmth and shelter provided. As the weather begins to warm up in March, the bats start emerging, usually becoming fully active by May.

Bats are a vital part of our native wildlife, and occupy a range of habitats, from wetlands and woodlands to urban environments. They are important for monitoring purposes, as they are very sensitive to changes in the environment, and can therefore tell us a lot about the state of the local environment.

Bat populations have been monitored for many years, and the Department for the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) recognises 11 out of the 17 UK bat species as biodiversity indicators and monitors their populations to understand our environmental health.

Birds

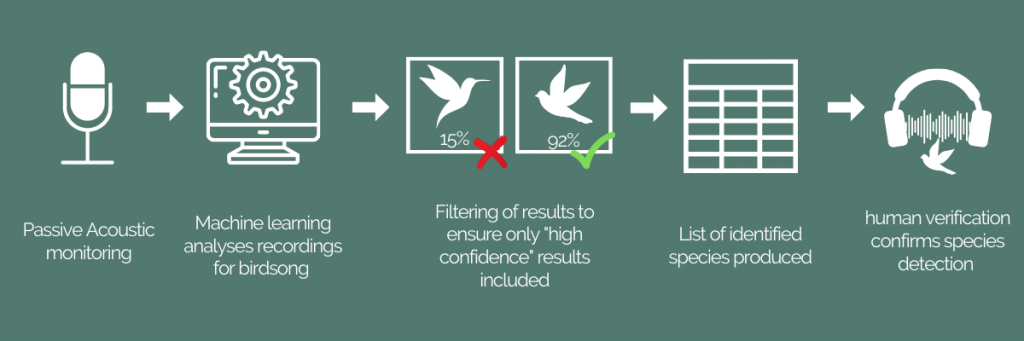

Bird identification can often be made by birdsong alone, and using passive acoustic monitoring equipment can be a very powerful way to survey a landscape over an extended period of time.

| Species | Number of high confidence* calls recorded |

| Goldcrest (Regulus regulus) | 1440 |

| Wren (Troglodytes troglodytes) | 399 |

| Chiffchaff (Phylloscopus collybita) | 207 |

| European Robin (Erithacus rubecula) | 188 |

| Tawny Owl (Strix aluco) | 126 |

| Long-tailed tit (Aegithalos caudatus) | 109 |

| Ring-necked Pheasant (Phasianus colchicus) | 104 |

| Treecreeper (Certhia familiaris) | 66 |

| Coal Tit (Periparus ater) | 66 |

| Spotted Flycatcher (Muscicapa striata) | 50 |

| Buzzard (Buteo buteo) | 42 |

| Nuthatch (Sitta europaea) | 27 |

| Raven (Corvus corax) | 24 |

| Eurasian Siskin (Spinus Spinus) | 20 |

| Great Spotted Woodpecker (Dendrocopos major) | 19 |

| Blue tit (Cyanistes caeruleus) | 15 |

| Hawfinch (Coccothraustes coccothraustes) | 10 |

| Great tit (Parus major) | 7 |

| (Barn) Swallow (Hirundo rustica) | 7 |

| Wood Warbler (Phylloscopus sibilatrix) | 6 |

| Dunnock (Prunella modularis) | 4 |

| Jay (Garrulus glandarius) | 4 |

| Northern Goshawk (Accipiter gentilis) | 3 |

Key Species

In 2018 the UK woodland bird index was 29% below its 1970 value. In the short term, between 2012 and 2017, the smoothed index decreased by 8%. Several of the identified species highlighted below have experienced serious decline in population in recent years, with three species (Hawfinch, Spotted Flycatcher and Wood Warbler) on the red list species of conservation concern (BoCC4).

Source: British Trust for Ornithology, Defra, Joint Nature Conservation Committee, Royal Society for the Protection of Birds.

The Tawny Owl can be easily detected through its distinctive male and female calls throughout the night. You can listen out for the characteristic ‘hoo-hoo’ call of the male and the shrill ‘kew-wick’ of the female in response. They have sadly suffered a 38% population decrease between 1970-2018.

As the name suggests, the Spotted Flycatcher‘s is an adept mid-air hunter of insects, and its diet includes butterflies, moths, damselflies and craneflies. Their populations have decreased dramatically, with a fall of 87% between 1970 – 2018. making it a red list species of conservation concern

The Wood Warbler can often heard trilling through the treetops, gracing our woodlands with its song during the summer, before migrating to Africa for the winter. The Wood Warbler has also seen sharp decrease in population, with a 63% population decrease between 1970-2018, making it also a red list species of conservation concern.

Want to learn more about biodiversity monitoring, and how you can observe and enjoy the wildlife around you? Follow us on social media or on our mailing list to learn more!